How to Find Ramps in the Wild

There are few things I enjoy more than foraging for ramps in the spring. Dense carpets of greens popping up after a long winter, the woods coming alive, and beautiful spring weather: it’s all fantastic.

I’m incredibly fortunate to spend time in places like this:

One of my favorite things about ramps: these places are pretty straightforward to find if you know where to start. In this post I’m going to discuss two different approaches to finding dense colonies of ramps like this.

NOTE: please take considerable effort to harvest ramps sustainably. They take a long time to grow and they are in great demand in many regions, so please be thoughtful when harvesting the full plants.

What Kind of Habitat We Should Look For

First things first, what kind of habitat should be look for when seeking wild ramps?

The easiest way to look for ramps is to find the trees that they most commonly associate with. Here’s what the U.S. Forest Service says about trees that ramps love in their guide on forest farming ramps:

Ramps grow best under hardwood trees such as beech, birch, maple, tulip poplar, buckeye (Aesculus sp.), basswood, hickory (Carya sp.), and oak (Quercus sp.). They do not grow well under conifers.

This is very helpful, but it still gives us a rather large list of trees to look for.

If we’re looking for the absolute best habitat to start with, then The Meat Eater team singles out maples in their guide for foraging for wild ramps:

Hardwood forests with rich, moist, well-drained soil are reliable and maple stands always seem to be a gold mine for me. I’ve also found that where trout lilies emerge, ramps are not far away.

Alright, there we go: mature maple stands are our best place to start. Given that they mention well-drained soils as being best suited for ramps, we should probably focus on sugar maples, as red maples tend to prefer wet feet.

Finding Ramps With Mature Sugar Maple Stands

Why am I looking to start our search out with a single species of tree? The Forest Service again comes into play, this time with two datasets that provide the approximate densities of hundreds of species of trees across the continental United States.

I’m going to walk you through using each dataset to find mature groves of sugar maples. The different datasets have some noteworthy differences, and it’s covered in greater detail in the above article.

Using the Tree Species Metrics Dataset to Find Sugar Maples

First, we’ll pull up the sugar maple density layer from the Tree Species Metrics dataset.

Load the Map and Find High Density Signal

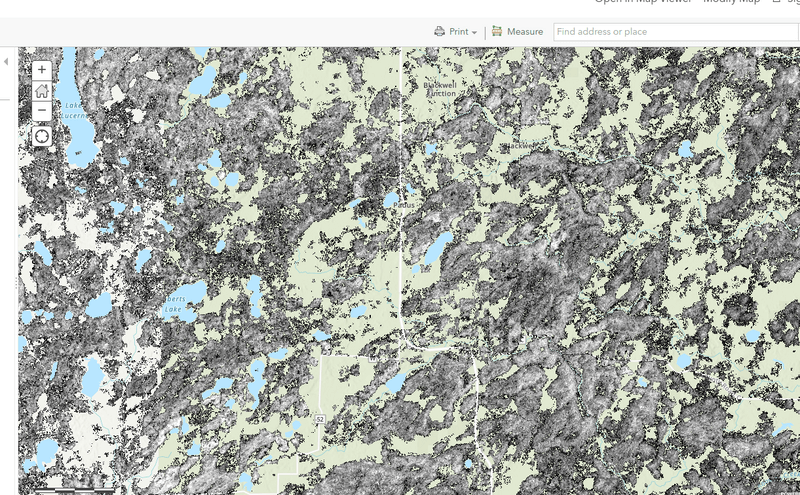

Load the map from the link and then zoom into your region. Assuming you have decent stands of sugar maples in your area, you might be greeted with something like this:

This map is showing the basal area of sugar maples, and you can understand basal area as a measurement of volume that is a species of tree. So keep this in mind: high volume doesn’t necessarily mean it is a mature stand.

The scale is this: the higher the volume for a stand, the closer to white it is. So in the below map we would treat this highlighted stand as the most dense one present:

There is one negative associated with this dataset: it’s a bit old. The data is from 2002, which isn’t terribly old in forest terms, but a lot can happen in more than 20 years. This data won’t reflect any logging or natural disasters that might have occurred since 2002, so keep that in mind.

Using the Individual Tree Species Parameter Maps

Next up, we’ll talk about using the Individual Tree Species Parameter dataset to find mature stands of sugar maples.

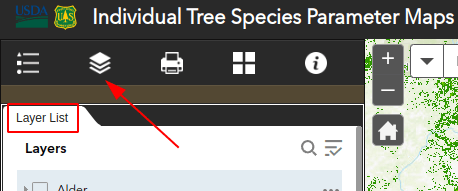

Click that link to load the map and then you’ll need to open the ‘Layer List’ tab found here:

Once there, you’ll want to uncheck the ‘Ash’ layer group and then do the following:

- check the Maple group

- uncheck the ‘maple spp.’ layer

- check the ‘sugar maple’ layer

- check whatever metric you’re interested in under the sugar maple group

The default will be the basal area, which you’ll remember was the metric we used in the last dataset. This is useful, but we’re going to want to explore the other metrics to help us find the mature stands more easily.

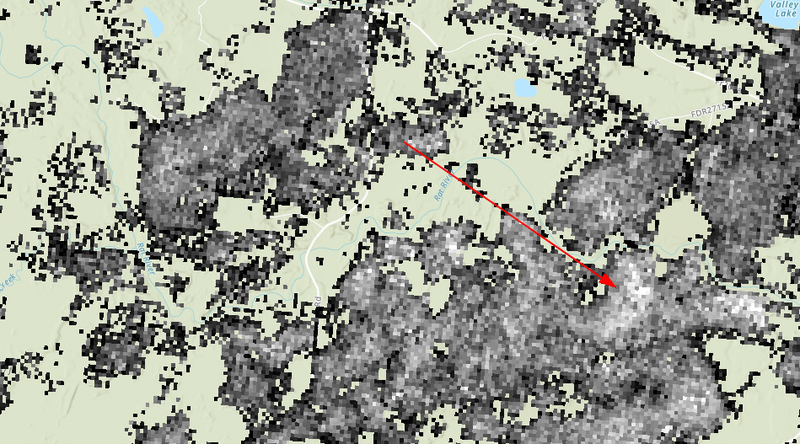

There is one caveat to using this dataset, and you’ll probably have already noticed it: the pixel size is significantly larger. Don’t get me wrong, this is still a very useful map, but we’ll just need to keep that in mind as we go.

As we’re looking for a mature grove of sugar maple trees, the simplest combination I would look for would be the following:

- a high percentage of basal area (note: not the basal area layer, the percent basal area)

- a high quadratic mean diameter

This combination should indicate that there is a dominant stand of sugar maple trees that are relatively large in comparison to the other areas.

Note that the scales for this map are fairly sensible: red and orange indicate higher numbers, while green is the lower end of the spectrum. Just like a radar map.

Also, understand that if you select two different metrics at the same time (like selecting both the percent basal area and quadratic mean diamter), then they will be superimposed on each other. I find it easiest to view one metric at a time. It’s not terribly convenient, but it works.

Checking if the Land is Public

You might be thinking, “yeah, it’s great that I can see where sugar maples are distributed, but how do I know if the land is public?” and that’s totally fair.

The best solution is to pull up the OpenStreetMap basemap for each dataset. It’s not a perfect solution, but this basemap shows the boundaries of public lands. It gets a little tricky when you’re looking at something like a National Forest where the majority of the land is public, but it’s a great free option (and who loves free more than foragers?).

Finding Ramps with Satellite Imagery From the Spring

So we covered the method of using sugar maple density maps to look for wild ramps, but there’s an even easier method. It just requires a little bit of dumb luck, but it’s the way I find my best spots for ramps.

Here’s the deal: if any of the high-quality satellite image sources (e.g. Google Maps, Bing, etc.) are composed of images taken during peak ramp season, then you should be able to see a “green haze” on the forest floor with leafless trees present.

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

Can you see the green haze and leafless trees that I’m talking about? There may be many understory species contributing to that, but I can assure you that the vast majority of color is from ramps in this specific case.

Now, this does require a fair bit of luck to get, but I thought it was worth pointing out, if only for the novelty.

Checking the Date With Google Earth

Google Earth Pro might be worth checking out if you strike out with the default satellite maps. First of all, they very conveniently provide the imagery date at the bottom of the screen:

And be sure to check the ‘wayback imagery’ tool at the top to search for more optimal images if you’re not having any luck. In my experience the imagery will likely need to be from 2010 at the latest because of resolution, but it’s worth a shot.

Conclusion

Thanks for taking the time to read this post. I hope it was interesting and could be helpful in your pursuit of our favorite woodland onion.